As part of Celebrate Learning Week and explorASIAN festival, Celebrate Student Research: Games in Asia was successfully held on May 18, 2021. Hosted by Saeyong Kim of Asian Library and moderated by Dr. Christina Laffin of the Department of Asian Studies, the session attracted an audience of 40 people at UBC and beyond.

As part of Celebrate Learning Week and explorASIAN festival, Celebrate Student Research: Games in Asia was successfully held on May 18, 2021. Hosted by Saeyong Kim of Asian Library and moderated by Dr. Christina Laffin of the Department of Asian Studies, the session attracted an audience of 40 people at UBC and beyond.

Over the decades, Asian Library has been providing support for students, scholars and community members who conduct research on Asia and Asian heritage. We are pleased to create opportunities particularly for emerging new researches to showcase their excellent work. This year, four presenters from UBC including Bianca Chui (History), Romi Kim (Art History, Visual Art & Theory), Tianyu Li (Asian Studies) and Taranjit Singh Dhillon (Asian Library) discussed a wide range of topics from traditional games to the sociocultural impact of digital gaming. Click the tabs below to explore!

Bianca Chui is graduating with BA in Honours History and is an incoming MA student in the Department of Asian Studies. Her thesis focused on the intersection between print culture and food culture by examining sugoroku in Edo Japan. As the event coordinator at the Centre for Japanese Research, Bianca organized over a dozen events of different nature in the 2020-21 academic year. Below is the abstract adapted from chapter two of her thesis Travel Through Tastebuds and Fingertips in Edo Japan: A Study of Shinpan gofunai ryūkō meibutsu annai sugoroku.

Eating Your Way Through Sugoroku: Imaginary Travel in a Japanese Board Game

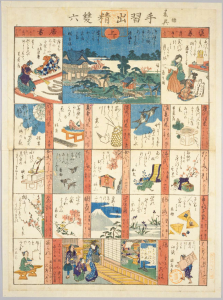

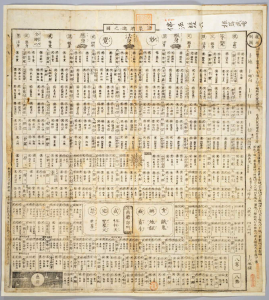

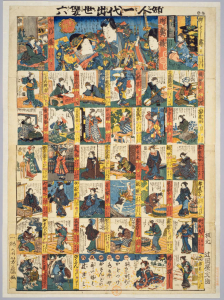

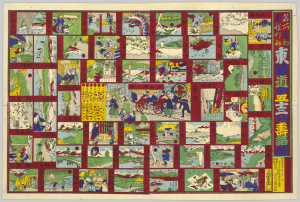

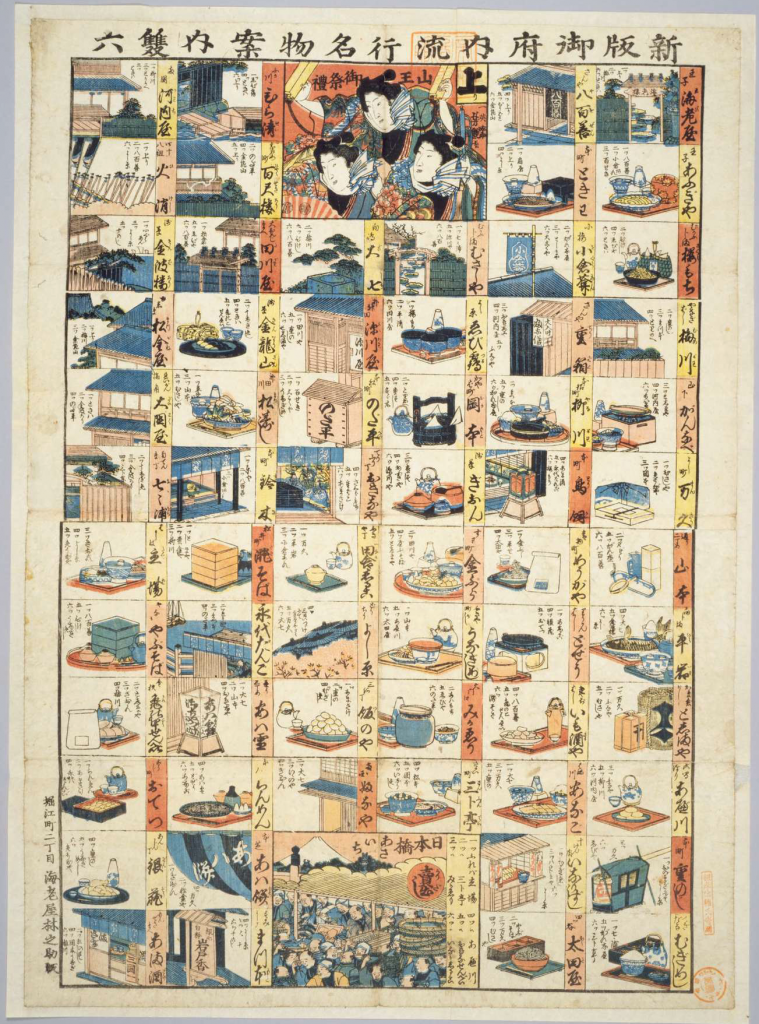

Like other forms of entertainment, games allow players to escape their mundane reality and immerse themselves in the imaginary worlds within. Before the development of video games in Japan, there was a type of board game called sugoroku. It appeared as early as the thirteenth century, and became more popular during the Edo period (1600–1868) with advances in woodblock printing technology. Sugoroku are somewhat similar to “snakes and ladders” games, with a player aiming to reach the final square before competitors. These games were often based on themes that were related to Buddhism, theatre, and travel. Shinpan gofunai ryūkō meibutsu annai sugoroku (ca. 1850 or 1852) is one example of sugoroku that features landmark restaurants and food items that existed in the city of Edo.

In this paper, I will consider how sugoroku fostered conceptual travel through the depiction of famous foods associated with specific locations or restaurants. I will focus on culinary examples of “famous things” (meibutsu) identified in these games. Sugoroku board games represented physical environments (like locations along a route) while also enabling players to create their own game worlds. Players could thus learn about famous sites and foods while also undertaking armchair journeys to these locations which existed both physically and in the mind’s eye.

Although many sugoroku feature a spiral-like path in which the player starts at one corner and advances towards the goal square in the centre, the sugoroku examined here is a “jumping” sugoroku where each square in the game gives specific instructions as to which square the player should proceed to when they throw a certain number. The elements of chance and uncertainty within a game of sugoroku allows for infinite versions of game paths. Depending on the number they throw, each player will experience a different path. Through repeated playing of the game, the players can embark on variations of gastronomic journeys.

This paper will examine consumable famous goods (or meibutsu) associated with set shops or locations as depicted in one particular sugoroku, the Shinpan gofunai ryūkō meibutsu annai sugoroku. I will focus on the “cherry rice-cakes” (sakura mochi) travellers purchased in front of the temple Chōmeiji as one example that demonstrates the intersection of food culture and travel culture as an object of play.

Keywords

Games, sugoroku, early modern Japan, meibutsu, food culture, travel culture

Utagawa Yoshitsuya 歌川芳艷. Shinpan gofunai ryūkō meibutsu annai sugoroku 新版御府内流行名物案内双六 [Sugoroku on popular specialties within Edo, new edition], Edo: Ebiya Rinnosuke, ca. 1850-1852. Multicoloured woodblock print, 69 x 49.8 cm. Courtesy of the National Diet Library, Tokyo.

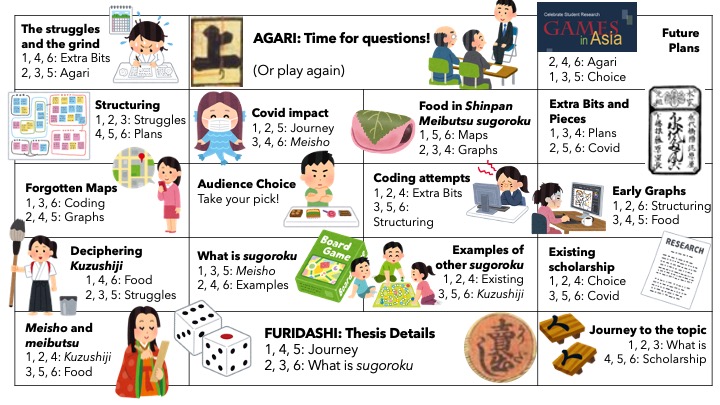

Bianca’s thesis journey sugoroku

Additional Resources

The following is a list of resources about Sugoroku in addition to Bianca’s presentation.

Sugoroku as a teaching and learning resource

Japanese Travel Literature and Culture (ASIA 453) is a course offered by the Department of Asian Studies at UBC. In Term 2 of Winter Session 2020-21, guided by Dr. Christina Laffin, ASIA 453 students deepened their understanding of travel culture in Japan before the modern period (before the late nineteenth century). As part of their course work, the students created their own travel-themed sugoroku! Check out their creations!

Jordan Embree and Ann Marie Davis at the Ohio State University has created Atomic Gameboard 原子双六, a digital exhibit that offers a close viewing and translation of a 1949 Japanese fold-out gameboard print (sugoroku) entitled Genshi Sugoroku (原子双六) held at the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum of The Ohio State University Libraries.

More Sugoroku images

Interested in looking at more sugoroku? Below are some of the examples from collections around the world.

김새로미, Romi Kim or Skim in drag (he/she/they) is a queer, genderfluid, second generation Korean living on unceded Musqueam, Tsleil-Waututh and Squamish first nations. They received their BFA in Visual Arts and Gender Studies from the University of Victoria and are currently an MFA candidate at UBC. Kim position themselves in understanding their identity as a process, a set of verbs rather than a noun or adjective. Kim’s practice explores intergenerational effects of colonialism, gender, and storytelling methods through affect and emotion. Currently they are researching the traditional Korean game Hwatu (introduced to Korea by Japan), Hanja (Sino Korean derived from Chinese), and the myth of Paridegi (the first Shaman in Korea). Installation, video, performance, bookmaking and drag are some of the mediums they work within.

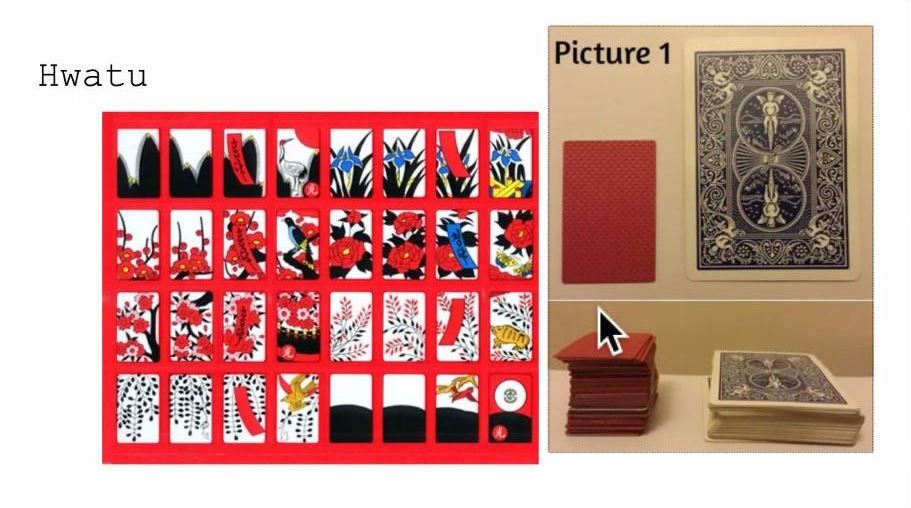

Hwatu

Romi presented on a traditional Korean card game called Hwatu (화투; hwah- too; 花鬪; Flower Fight), which was introduced to Korea during the Japanese occupation. They shared their personal relationship with the game as well as other people’s experiences with the game that they have gathered from interviews. They spoke on various games with the hwatu cards, the way the deck has changed over time, and cultural as well as historical aspects of the game.

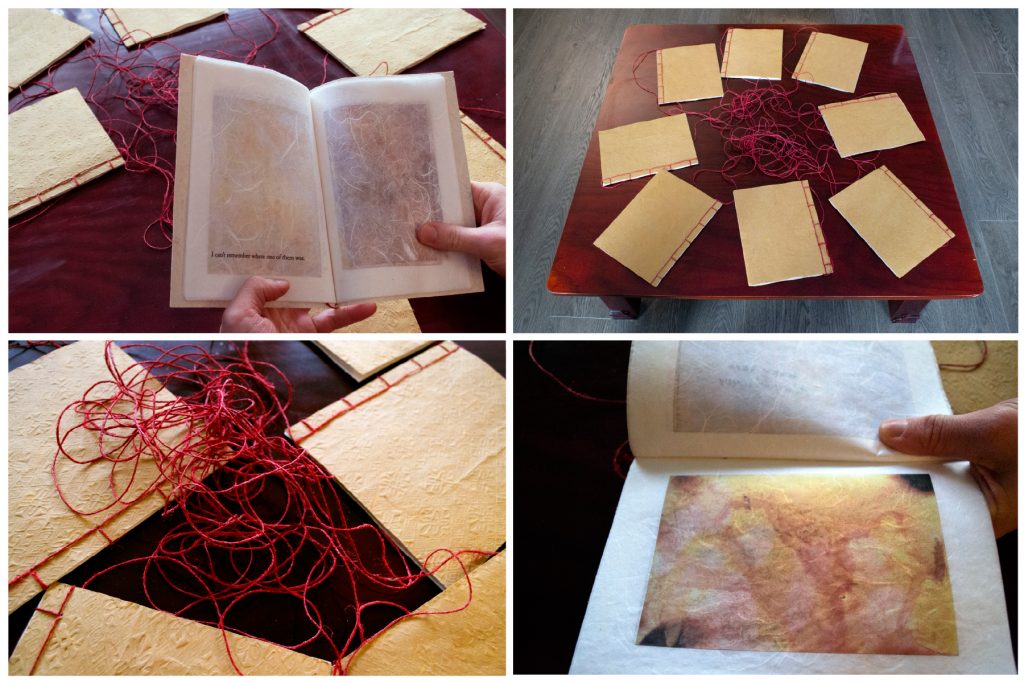

Bookmaking project

In addition to their research on Hwatu, Romi is working on the bookmaking project 辛. They explore deconstructing their own story through their personal memories as well as containing it in traditional Korean books with culturally hybrid untraditional techniques. Romi deliberately writes only in Korean for most of the books to practice the Korean language and give privilege in access to Korean readers.

⾟

⾟

⾟ in Hanja : Spicy, pungent; ⾟ in Kanji : barely; narrowly; only just; with difficulty; 辛 in Chinese : Pain; suffering

These books are dedicated to 우리 엄마.

辛 is an in progress work that started in 2020. The work entails scans of destroyed photographs from 2008- 2012 printed onto Hanji (mulberry) paper order from Gmarket with my Mother’s help. It was printed using the “experimental printer” at UBC with PRC technician’s Ian Craig and Vicky Mo’s help. The Hanji paper was carefully taped onto dollar store paper with green painter’s tape and then cut to standard traditional Korean book size with the PRC paper cutter. 100% organic hemp used to bind the book was bought from Michael’s along with Cherry Red Rit dye and beeswax. The red hemp string was thread with Natalie’s needle to bind the books. The covers and binding were created from the journal article “Korean traditional bookbinding”. A wooden block was hand drawn and then carved with Andy Keech’s help on the C router in the UBC woodshop. Wheat paste was made from T&T wheat flour and then used to paste multiple pages of Hanji together to create the covers. It was then embossed in the PRC with Ian’s help. This project would not have been possible without https://stephruejournal.wordpress.com/. Red corrections were written by Mom and June Emo. All mistakes in pencil are my own.

Tianyu Li received his BA in History with a Minor in Philosophy. He is currently pursuing a MA in the Department of Asian Studies, supervised by Dr. Sharalyn Orbaugh and Dr. Renren Yang. His research focuses on transnational culture and media studies, it pays attention to the question of (post)human self-identity and desire in Chinese video games in relation to Japanese manga and anime. Tianyu also has interests in the representation of evolutionary thinking in video games. Below is the abstract and outline of his presentation on cloud gamers (yunwanjia).

Vicarious Players in Real Communities: Cloud Gamers (Yunwanjia) in Chinese E-Sports Fandom

Cloud as a powerful metaphor of a groundless, swift, capacious, and benevolent entity is ubiquitous in our world today in the form of cloud computing and storage. While cloud-gaming services—as in streaming video games across platforms—remain in the preliminary stage, Chinese-speaking player communities coined the term yunwanjia 云玩家, literally “cloud gamers/players,” to refer to individuals who can hardly be categorized as conventional players. Rather than users of cloud gaming services, yunwanjia refers to individuals who experience and interact with games not through playing but through watching live-stream or prerecorded video content online. This presentation discusses the origin and sociocultural significance of yunwanjia as a social construct in the context of Chinese esports fandom, it argues that cloud gaming is embedded in public discourses of video games. By placing the conception of yun 云 (cloud) into a discursive history, my discussion makes the case that the nearly omnipresent screens installed in infrastructures as well as possessed by individual users construct public spaces that foster cloud gaming. I take the League of Legends esport spectators in China as the subject of my case study and explore how yunwanjia as a social construct creates, shapes and alters social interactions among urban Chinese by engaging with Foucault’s theory of heterotopia. In doing so, this presentation challenges the existing scholarships on cloud gaming that situates the phenomenon exclusively into industry studies about Chinese video games and esports. It suggests that yunwanjia needs to be studied with considerations of philosophical contemplations beyond simple industry studies.

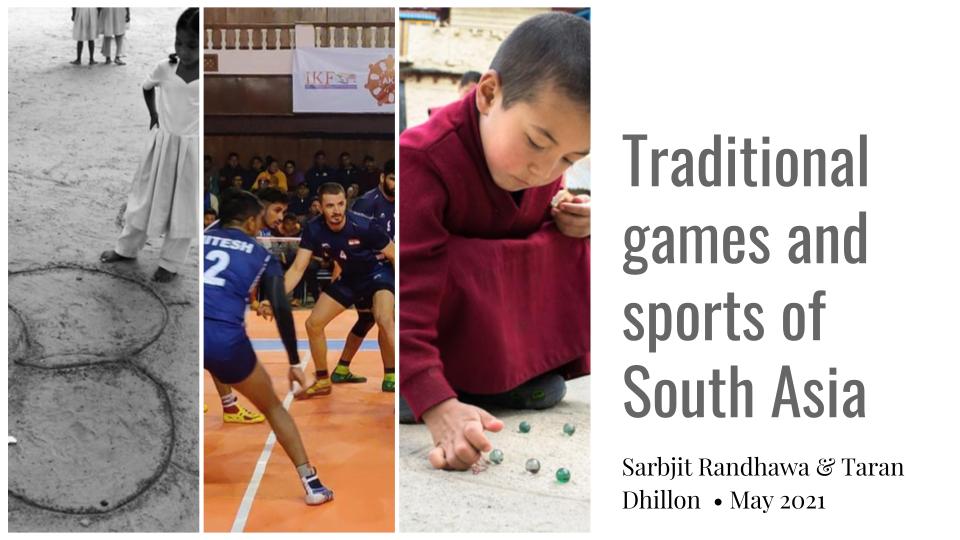

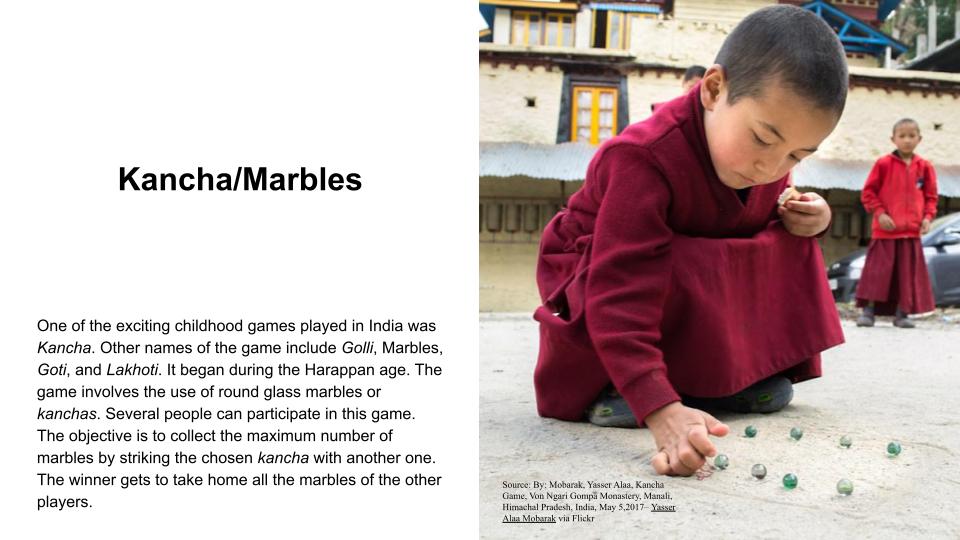

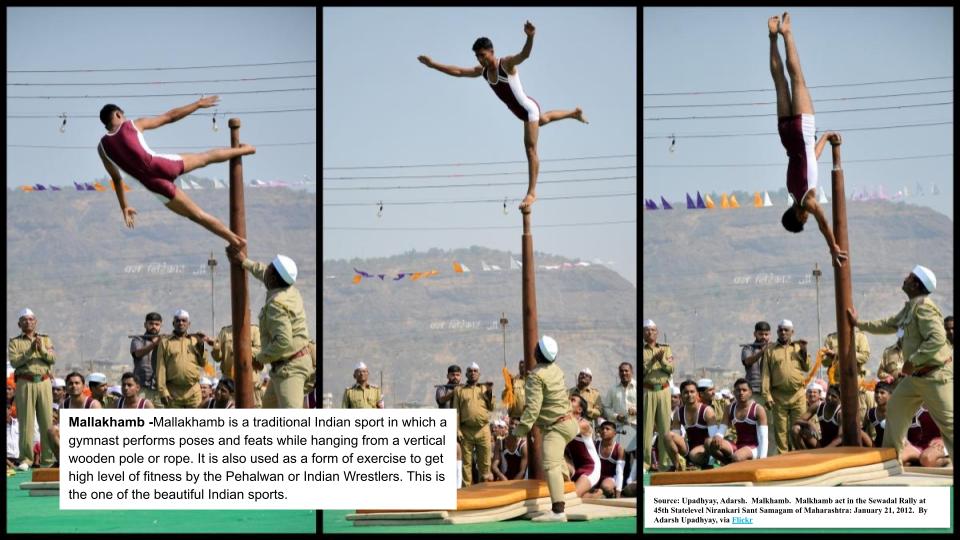

Taranjit Singh Dhillon is a freelance journalist, engineer & currently works at the Asian Library. He graduated from the Graduate School of Journalism, UBC Vancouver in 2018 and has worked briefly with CBC Indigenous, Canadian not-for-profit think-tank Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada, Vancouver, Canada Eurasia Russia Business Association, Indian Railways and Jyotirgamaya, a community radio station. His research interests are traditional games of South Asia, geopolitics and the Arctic region security. Taranjit shared below a few slides from his presentation and you can read the entire file here.

Culin, Stewart. Korean games with notes on the corresponding games of China and Japan. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 1895.

“Famous Places, People, and Social Customs on Paper: Sugoroku Board Games from the Edo Period, Part 1, Famous Places,” National Diet Library Newsletter, no. 234 (2020): 5-11.

“Famous Places, People, and Social Customs on Paper: Sugoroku Board Games from the Edo Period, Part 2, People,” National Diet Library Newsletter, no. 236 (2021): 6-15.

“Famous Places, People, and Social Customs on Paper: Sugoroku Board Games from the Edo Period, Part 3. Social Customs,” National Diet Library Newsletter, no. 237 (2021): 1-9.

He, Yunbo 何云波. Wei qi yu Zhongguo wen hua 围棋与中囯文化. Beijing: Ren min chu ban she, 2001.

Kazāka, Kirapāla. Loka-kheḍāṃ te Pañjābī sabhiācāra. Paṭiālā: Pablīkeshana Biūro, Pañjābī Yūnīwarasiṭī, 2005.

Kobayashi, Shōjirō 小林祥次郎. Asobi no gogen to hakubutsushi 遊びの語源と博物誌. Tokyo: Bensei Shuppan, 2015.

Kwon, Hyun Ju 권현주. “화투의 놀이문화기호 재매개 과정 분석-마조, 골패, 수투, 카르타, 하나후다의 내러티브를 중심으로- Analysis on Re-mediacy Process of Play Culture of Hwatu -Focusing on Narrative of Mahjong, Domino, Sutu, Carta and Hanahuda-,” 日本語文學 Korean Journal of Japanese Language and Literature, no. 72 (2017): 383-404.

The Landmarks of Edo in Color Woodblock Prints. National Diet Library. (*Some of the places depicted in meisho or dōchū sugoroku can be found on this online exhibit of nishiki-e [colour woodblock prints] depictions of Edo landmarks with annotated descriptions.)

Mādapurī, Sukhadewa. Panjaba diam loka khedam. 1975.

Moskowitz, Marc L. Go nation: Chinese masculinities and the game of weiqi in China. Berkeley : University of California Press, [2013].

Namiki, Seishi 並木誠士. Edo no yūgi: kaiawase, karuta, sugoroku 江戸の遊戯: 貝合せ・かるた・すごろく. Kyoto: Seigensha, 2007.

No, Sung-hwan 노성환. “한국에 있어서 화투의 전래와 변용 Introduction and changes of Hwatu in Korea,” 일어일문학 Journal of Japanese Language and Literature, no. 80 (2018): 245-270.

Salter, Rebecca. Japanese popular prints: from votive slips to playing cards. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2006.

Singh, Sarwan. Kheḍāṃ dī dunīā. Samāṇā: Saṅgama Pabalīkeshanaza, 2012.

Singh, Sarwan. Pañjāba de ūgghe khiḍārī : [wārataka]. Samāṇā: Saṅgama Pabalīkeshanaza, 2013.

Singh, Sarwan. Pañjāba dīāṃ desī kheḍāṃ. Paṭiālā: Pabalīkeshana Biūro, Pañjābī Yūnīwarasiṭī, 1996.

Szablewicz, Marcella. Mapping digital game culture in China from Internet addicts to esports athletes. Cham: Springer International Publishing : Imprint: Palgrave Macmillan, 2020.

Takahashi, Junji 高橋順二. Nihon esugoroku shūsei 日本繪双六集成. Tokyo: Kashiwa Bijutsu Shuppan, 1994.

Zhang, Qingwen 張晴文. You xi, hu dong 遊戲・互動. Taibei Shi: Xing zheng yuan wen hua jian she wei yuan hui, 2003.

Zhang, Ru’an 张如安. Zhongguo wei qi shi 中国围棋史. Beijing Shi: Tuan jie chu ban she : Xin hua shu dian Beijing fa xing suo fa xing, 1998.